- 12 min read

From Alpha to Beta: How Artificial Sweeteners Destroy the Gut Bacteria Behind Male Dominance

A 2022 Cell Reports study proved gut bacteria control social dominance. Artificial sweeteners kill those exact bacteria. The science on what that means for your edge.

A few years ago, researchers at Hefei University of Technology in China ran an experiment that should give every performance-minded man pause. They took pairs of rats, identified which animal was socially dominant and which was subordinate, and then analyzed their gut bacteria. The dominant rats harbored a distinct microbial signature, rich in bacteria that produce a short-chain fatty acid called butyrate. When the researchers disrupted the gut microbiota of the dominant rats with antibiotics, those animals lost their competitive edge and slipped into subordination. Then came the critical finding: transplanting fecal microbiota from dominant rats into subordinate ones restored the recipients to social dominance. A single bacterium, Clostridium butyricum, was sufficient to do it (1).

The study, published in Cell Reports in March 2022, traced the mechanism from the gut all the way to the brain. Butyrate produced by intestinal bacteria traveled to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), a brain region that governs decision-making, social behavior, and executive function, where it modulated an enzyme called HDAC2 (histone deacetylase 2). By inhibiting HDAC2, butyrate altered gene expression in specific neurons, strengthened synaptic connections, and effectively rewired the brain circuitry that determines competitive outcomes (1). The chain of causation was elegant and direct: the right gut bacteria produce butyrate, butyrate remodels the prefrontal cortex, and the animal behaves with greater confidence and social assertiveness.

This raises an uncomfortable question for the millions of men who consume artificial sweeteners daily under the assumption that they are a harmless substitute for sugar. If the bacteria that produce butyrate are the biological foundation of mental sharpness and competitive drive, what happens when something in your diet systematically destroys those bacteria?

The Sweetener in Your Protein Shake May Be Doing More Harm Than Sugar

Walk into any supplement store, gas station, or office break room and you will find artificial sweeteners everywhere: in protein powders, pre-workout formulas, “zero calorie” energy drinks, flavored waters, sugar-free gum, and the yellow, blue, and pink packets next to the coffee machine. The pitch is straightforward: all the sweetness with none of the metabolic cost. For men watching their body composition, managing blood sugar, or simply trying to cut empty calories, the logic seems sound.

The evidence tells a different story. Over the past decade, a mounting body of research has documented that non-nutritive sweeteners, including sucralose (Splenda), aspartame (Equal, NutraSweet), saccharin (Sweet’N Low), and acesulfame potassium (Ace-K), alter the composition and function of the gut microbiome in ways that mirror the very metabolic problems they are supposed to prevent (2, 3, 4). The mechanism is not subtle. These compounds reach the large intestine largely intact, where they come into direct contact with the bacterial communities responsible for producing short-chain fatty acids, maintaining the gut barrier, and communicating with the brain through the vagus nerve and systemic circulation (4).

A landmark 2022 randomized controlled trial published in Cell, led by Jotham Suez and colleagues at the Weizmann Institute of Science, provided the most rigorous human evidence to date. The researchers enrolled 120 healthy adults who did not habitually consume artificial sweeteners and randomly assigned them to receive sachets of saccharin, sucralose, aspartame, or stevia, all at doses below the FDA-approved acceptable daily intake, for two weeks. Control groups received glucose or no supplement. The results were striking: all four sweeteners significantly altered the composition and metabolic function of participants’ gut and oral microbiomes. Saccharin and sucralose went further, significantly impairing glycemic responses to glucose tolerance tests. When the researchers transplanted fecal microbiota from the human “responders,” those whose glucose tolerance worsened most, into germ-free mice, the mice developed the same glycemic impairment, confirming that the metabolic damage was being transmitted through the microbiome itself (2).

That last point deserves emphasis. The glucose intolerance was not caused by the sweetener acting directly on the pancreas or liver. It was caused by the sweetener reshaping the gut bacteria, and those reshaped bacteria then producing the metabolic dysfunction. The gut microbiome was the mediator, and the sweetener was the disruptor.

Butyrate Under Siege: How Sweeteners Starve Your Brain’s Supply Chain

The connection back to the Wang et al. dominance study becomes clear when you examine which bacterial populations artificial sweeteners suppress. Multiple animal and human studies have documented that sucralose, aspartame, saccharin, and acesulfame-K reduce populations of bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes phylum, the group that includes the most prolific butyrate producers, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, and members of the Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families (3, 4). A study using the artificial sweetener neotame in male mice found significant gut microbiome alterations over just four weeks, including decreased Firmicutes, reduced diversity, and a measurable decline in butyrate fermentation capacity (4). Sucralose has been shown to enrich potentially harmful families like Enterobacteriaceae, bacteria associated with gut inflammation and dysbiosis, while simultaneously depleting the butyrate-producing taxa that Wang and colleagues identified as the microbial signature of dominance (3, 4).

The implications cascade upward from the gut to the brain. Butyrate is not merely a gut health molecule. It functions as one of the primary chemical messengers between the intestinal microbiome and the central nervous system. In the brain, butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase inhibitor, the same mechanism Wang’s team identified in the mPFC, which means it epigenetically modifies gene expression by loosening chromatin structure and permitting transcription of genes involved in synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, and neurotransmitter regulation (5, 6). Research has shown that butyrate increases levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, stimulates neurogenesis, attenuates neuroinflammation, and modulates the expression of enzymes critical for serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline synthesis (5, 6, 7). In animal models, sodium butyrate administration has reversed depressive-like behaviors, improved cognitive performance, and restored social engagement, findings that align precisely with the dominance effects observed in the Cell Reports study (6, 7).

When artificial sweeteners reduce butyrate-producing bacteria, they are not just affecting digestion. They are potentially compromising the epigenetic machinery that keeps the prefrontal cortex sharp, emotionally regulated, and socially engaged. For a man in his forties, fifties, or sixties competing in a demanding career, maintaining physical performance, and needing his decision-making faculties at full capacity, this is not a trivial concern. As we explore in Lose Your Edge, Risk Your Heart, the slow erosion of physical and cognitive capacity in men often begins long before it becomes clinically obvious, and the gut may be where that decline quietly starts.

Stevia Is Not the Safe Harbor You Were Promised

One of the most common responses when men learn about the risks of artificial sweeteners is to switch to stevia, marketed as a “natural” zero-calorie sweetener derived from the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana. The reasoning seems sound: if the problem is synthetic chemicals damaging gut bacteria, a plant-based alternative should be benign. The evidence, however, is more complicated than the marketing suggests.

The Suez et al. Cell trial included stevia (specifically rebaudioside A, the most commonly used steviol glycoside) as one of its four test sweeteners, and it found that stevia significantly altered gut microbiome composition and function, much like the synthetic sweeteners (2). While stevia did not impair glucose tolerance as clearly as saccharin and sucralose in that particular trial, the microbiome changes it induced were not neutral. A separate 12-week human study that examined stevia’s effects in detail found that after three months of daily consumption, participants showed significant downregulation of Butyricoccus, a butyrate-producing genus, and reduced levels of Blautia, a genus associated with the production of both butyric and acetic acids (8). The stevia group also showed a significant reduction in Megasphaera, another genus with species linked to butyrate production (8). Steviol glycosides have also been shown to inhibit the growth of Lactobacillus reuteri strains in a concentration-dependent manner, and one study found that stevia caused microbiota alterations similar to saccharin when administered alongside a high-fat diet (8, 9).

None of this means stevia is as harmful as sucralose or saccharin; the evidence suggests synthetic sweeteners are generally more disruptive than their plant-derived counterparts (4). But the notion that stevia is completely inert in the gut is not supported by the available data, and for men specifically focused on preserving butyrate-producing bacterial populations, even moderate interference with those communities carries downstream consequences for the gut-brain axis.

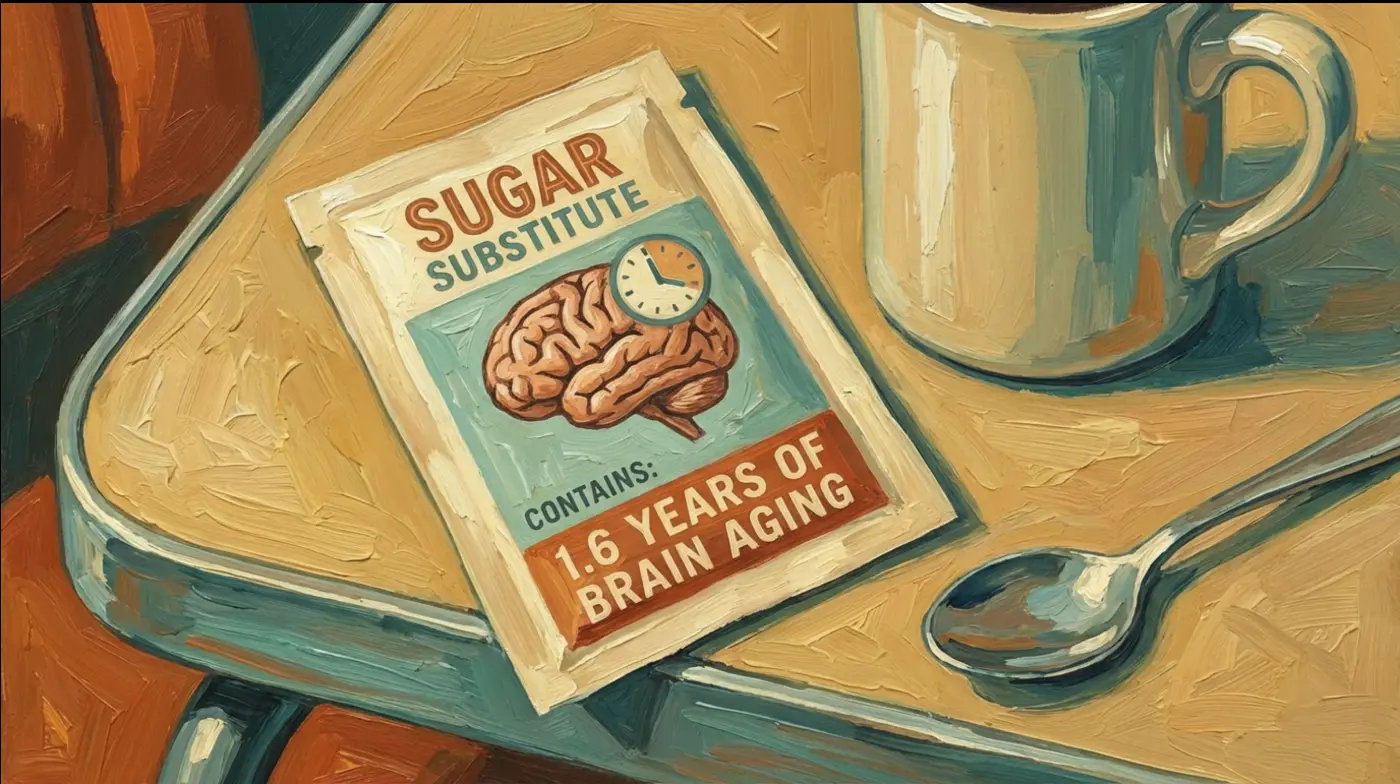

1.6 Years of Brain Aging in a Sweetener Packet

If the mechanistic evidence linking sweeteners to gut dysbiosis and reduced butyrate production seems abstract, the clinical outcomes research makes it concrete. In 2025, a prospective cohort study of 12,772 adults published in Neurology, the journal of the American Academy of Neurology, tracked cognitive function over eight years in relation to artificial sweetener consumption. The findings were sobering: participants who consumed the highest quantities of low- and no-calorie sweeteners showed a 62% faster rate of global cognitive decline compared to those who consumed the least. The researchers calculated this acceleration as equivalent to 1.6 additional years of brain aging. The decline was most pronounced in working memory and verbal fluency, cognitive domains governed by the prefrontal cortex, the same brain region where Wang and colleagues demonstrated butyrate’s effects on synaptic function and social dominance (10).

An accompanying editorial in Neurology titled “The Dark Side of Sweet” noted that while the study was observational and could not prove causation, the biological plausibility was strong, citing the established pathways through which sweeteners alter gut microbiota, promote neuroinflammation, and compromise blood-brain barrier integrity (11). The cognitive decline was more pronounced in participants under 60, precisely the age range where men are still building careers, managing teams, and competing at the highest professional levels, and was amplified in participants with diabetes, suggesting that metabolic disruption and cognitive decline may share a common microbial mediator (10). This aligns with emerging research showing that low testosterone itself increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, meaning sweetener-driven gut dysbiosis may be one of several converging forces eroding brain health in aging men.

Additional research reinforces these findings through complementary mechanisms. A 2024 study published in International Immunopharmacology documented that aspartame exposure triggered microglia-mediated neuroinflammation, the brain’s own immune cells attacking neuronal tissue, leading to measurable cognitive dysfunction in animal models (12). A separate line of research has linked the artificial sweetener erythritol to enhanced platelet reactivity and increased thrombosis potential, with cardiovascular implications published in Nature Medicine in 2023 (13), a finding that underscores the broader role of inflammation as a central force in cardiovascular disease. And a 2023 study in Scientific Reports found that learning and memory deficits produced by aspartame exposure in mice were heritable via the paternal lineage, raising the possibility that sweetener-induced cognitive impairment could affect the next generation (14).

The Metabolic Trap: How “Zero Calories” Can Still Make You Fatter and Sicker

The gut-brain axis damage from artificial sweeteners does not operate in isolation from metabolic health. A 2025 randomized, placebo-controlled, triple-blind trial found that 30 days of sucralose consumption in healthy lean individuals produced a 20.3% decrease in insulin sensitivity, a change mediated by shifts in gut microbiota composition and associated with a pro-inflammatory metabolic environment (15). This finding aligns with the earlier Suez et al. data and with animal research showing that aspartame combined with a high-fat diet promotes expansion of Enterobacteriaceae while reducing SCFA-producing taxa, creating a pro-inflammatory gut environment and endotoxemia, the leakage of bacterial toxins into the bloodstream (3, 4).

For active men over 35 who are using artificial sweeteners specifically to support body composition and metabolic health, this represents a cruel irony. The zero-calorie sweetener consumed to avoid insulin spikes may be producing insulin resistance through a different pathway entirely. Insulin resistance itself drives visceral fat accumulation, the inflammatory abdominal fat that further disrupts hormonal signaling and compounds every metabolic problem sweeteners are supposed to prevent. The man who puts sucralose in his morning coffee and drinks two diet sodas during the day is potentially degrading his insulin sensitivity, increasing systemic inflammation, depleting the butyrate-producing bacteria that support his prefrontal cortex function, and accelerating cognitive decline, all while believing he is making the healthier choice.

The distinction matters clinically. The metabolic damage from artificial sweeteners is not uniform across individuals. The Suez et al. trial identified clear “responders” and “non-responders,” with some participants showing pronounced glycemic impairment and microbiome disruption while others showed minimal change (2). This individual variability likely depends on baseline microbiome composition, diet quality, genetics, and other factors that are only beginning to be understood. But the existence of non-responders does not make sweetener consumption safe; it means that some men are more vulnerable than others, and there is currently no clinical test to determine which category you fall into before the damage accumulates.

What to Do With This Information

The research connecting artificial sweeteners to gut dysbiosis, reduced butyrate production, impaired cognition, and metabolic disruption is substantial and growing, though important caveats remain. Much of the mechanistic work comes from animal models, and the human trials, while well-designed, involve relatively short exposure periods and moderate sample sizes. The gut-brain axis field is still maturing, and the specific causal pathways linking sweetener-induced microbiome changes to long-term cognitive outcomes in humans will require years of additional study to fully map. The Wang et al. dominance study was conducted in rats, and while the gut-brain mechanisms it identified are conserved across mammals, direct extrapolation to human social and professional performance requires caution.

That said, the convergence of evidence across multiple independent lines of research, from rodent dominance hierarchies to human glucose tolerance trials to eight-year cognitive decline cohorts, paints a consistent picture. Artificial sweeteners disrupt the gut microbiome, particularly the butyrate-producing bacteria that serve as a critical communication link between the intestine and the prefrontal cortex. The downstream consequences touch cognition, mood regulation, insulin metabolism, inflammation, and potentially the very traits that define competitive performance in men.

For men who are serious about maintaining their edge, several practical steps follow from the evidence. First, audit your daily intake of artificial sweeteners. They accumulate from sources you may not be tracking, including protein supplements, flavored BCAAs, pre-workout formulas, sugar-free condiments, chewing gum, and “health” beverages. While you’re at it, examine the rest of your diet for compounds that quietly undermine male biology: soy is another common disruptor worth scrutinizing. Second, prioritize dietary fiber from diverse whole food sources (vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, fermented foods) to feed butyrate-producing bacteria directly. This is the single most evidence-supported strategy for maintaining a healthy gut-brain axis (5, 7). Third, if you are consuming sweeteners to manage weight or blood sugar, discuss the tradeoffs with your physician, particularly if you are over 40 or have a family history of metabolic disease or cognitive decline. The metabolic benefits of avoiding sugar do not automatically transfer to its chemical replacements.

The Mas Clinic approaches gut health as a fundamental pillar of men’s health optimization. We also recognize that evidence-based practice has real limitations: clinical trials exclude diverse populations, guidelines lag behind emerging science, and one-size-fits-all protocols ignore individual variability. That’s why our approach to disciplined optimization integrates the best available evidence with comprehensive individual assessment, systematic protocols, and continuous outcome measurement.

The research on artificial sweeteners and the gut-brain axis reinforces what we see clinically: that what happens in the gut does not stay in the gut. It shapes your metabolism, your mental clarity, your resilience under stress, and yes, your competitive drive. The men who take this seriously, who read the evidence and adjust accordingly, are the ones who maintain their edge into their fifties, sixties, and beyond. The science supports nothing less.

Ready to stop guessing and start optimizing? The Mas Clinic maps your gut health, metabolic function, inflammatory markers, and hormonal status through a comprehensive assessment designed specifically for men who refuse to settle for “normal.” Join the waitlist to be among the first to access our integrated men’s health protocol. Your biology isn’t waiting, neither should you.

References

-

Wang T, Xu J, Xu Y, Xiao J, Bi N, Gu X, Wang HL. Gut microbiota shapes social dominance through modulating HDAC2 in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cell Reports. 2022;38(10):110478. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110478

-

Suez J, Cohen Y, Valdes-Mas R, et al. Personalized microbiome-driven effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on human glucose tolerance. Cell. 2022;185(18):3307-3328.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.07.016

-

Cao Y, Liu H, Qin N, et al. Non/low-caloric artificial sweeteners and gut microbiome: from perturbed species to mechanisms. Metabolites. 2024;14(10):544. PMC11509705.

-

Arora K, Garg S, Engel L, et al. Disrupting the gut-brain axis: how artificial sweeteners rewire microbiota and reward pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025;26(20):10220. PMC12564633.

-

Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Bhatt RR. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neuroscience Letters. 2016;625:56-63. PMC4903954.

-

Coppola C, Ferranti L, Faralli A, et al. Beneficial effects of butyrate on brain functions: a view of epigenetic. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2024;64(20):6810-6828. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2137776

-

Du Y, He C, An Y, et al. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications. General Psychiatry. 2024;37(1):e101374. PMC10882305.

-

Singh DP, Singh J, Boparai RK, et al. Consumption of the non-nutritive sweetener stevia for 12 weeks does not alter the composition of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2024;16(2):296. doi:10.3390/nu16020296

-

Nettleton JE, Klancic T, Schick A, et al. Low-dose stevia (rebaudioside A) consumption perturbs gut microbiota and the mesolimbic dopamine reward system. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):1248. PMC6627124.

-

Melo van Lent D, Gokingco FT, et al. Association between consumption of low- and no-calorie artificial sweeteners and cognitive decline: an 8-year prospective study. Neurology. 2025;105(2):e214023. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000214023

-

The dark side of sweet (editorial). Neurology. 2025;105(2):e214129. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000214129

-

Dar NJ, et al. Aspartame-induced cognitive dysfunction: unveiling role of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and molecular remediation. International Immunopharmacology. 2024;131:111817.

-

Witkowski M, Nemet I, Alamri H, et al. The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk. Nature Medicine. 2023;29:710-718.

-

Jones SK, McCarthy DM, Vied C, Bhide PG. Learning and memory deficits produced by aspartame are heritable via the paternal lineage. Scientific Reports. 2023;13:1573.

-

Mendez-Garcia LA, et al. Sucralose consumption modifies glucose homeostasis, gut microbiota, Curli protein, and related metabolites in healthy individuals: a randomized placebo-controlled, triple-blind trial. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2025.

Was this article helpful? Let us know!